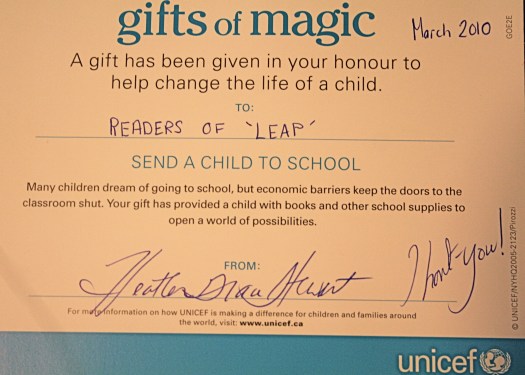

Leap, from the author of Where the Butterflies Go, is available for purchase at Lulu.com and Amazon stores worldwide. It’s also available on Kindle, Kobo, iBooks, and where all fine ebooks are sold. You can also order an autographed copy via Paypal. Contact the author at writer@hgrace.com. Half the proceeds from sales go to Hearts for Change – an Educational Project for orphaned children in Kenya.

Here’s an interview with the author from 2010:

Questions for a Poet, As Put to Seamus Heaney

Q: Some years ago, Seamus Heaney told an English journalist: “My notion was always that, if the poems were good, they would force their way through.” Is this now your experience?

HGS: Absolutely. Sometimes it comes through in a matter of minutes; other times, I write down a few lines, and the rest follows maybe a day or a few weeks later. But if it’s good, it all ends up on the page…and then typed into a document in my “Poetry in the works” file on my computer, and then, if I still like it after I’ve lived with it a couple weeks, I put it into a “Poetry to publish” file.

Q: Over the years, Heaney often quoted Keats’s observation, “If poetry comes not as naturally as leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all.” Is that just a young poet’s perspective?

HGS: I think so. It doesn’t always come naturally to me. Sometimes I just need to sit down and force myself to write. Stop listening to the whining voice; shut it out, and just “do it.”

Q: Does this mean that a poem essentially begins for you when you find a form?

HGS: A poem essentially begins for me when I’ve found my voice for it; the form takes shape with the voice.

Q: Is there a poetry time of day and a prose time of day?

HGS: Used to be I used my early mornings for poetry and at sunset, and prose anytime, but now that I am a mother, it’s when I have a notepad, pen, and that spare minute when I’m not being asked to wipe a bum or put Barbie’s head back on.

Q: I remember Anne Yeats saying that her father mumbled to himself when he started to write. Would the Stewart household know that a poem was coming on?

HGS: In my household my hubby can usually tell a poem (for kids or adults) is being born if he comes home at 6:30 p.m. and DD is beside me doing a puzzle; a grilled cheese or rice is burning on the stove, and I’m soaking wet; just out of the shower in a towel with a focused look on my face, typing at the computer, “Just a minute, honey I have this idea…” And he’s so cool about that. He’s used to me by now. Now my daughter’s getting in on it, too. She looks at my face sometimes and says, “Mommy, what? Do you have an idea? Tell me, tell me, what is it? ” I try hard to be in the moment with her as often as I can, but the kid is smart, she’s onto me…so I usually end up spilling, because I don’t like to talk down to her, and sometimes, just by explaining it to her, she helps me better formulate the idea. Just wait, you guys are going to love our kids poem, ‘Cats Can’t Cook!’

Q: Do you ever feel burdened by the sheer amount of work you know it will require to do justice to a particular inspiration?

HGS: All the time. All the time. Right now, I’m trying to write a poem that’s going to do justice to this amazing group of people I’ve met online, and become close to over a year and a bit. Some might guffaw that you can make special friendships online. I beg to differ. I don’t know how I’m going to write something that truly speaks to this experience I’ve had. I think maybe they’ll help me somehow, because a lot of them are writers…actually, I’ve dedicated LEAP in part to them.

Q: How can you tell a poem is finished?

When it stops shouting at me. 😉

Q: Do you keep a notebook of phrases and images for later use?

HGS: I have several notebooks, with penned poems/ ideas to type out later, and my images are saved on the computer by date.

Q: Does the poem come more quickly if there is a form? Would you be offended to be called a formalist?

HGS: I don’t think anyone would call me a formalist, but I definitely use techniques. Just not formally. Okay, seriously now, I’ve written haiku, tanka,

and Villanelles, using proper form. I just don’t like being weighed down by form. As Frank sang, I’ll do it my way 😉

Q: Do you have a preference for pararhymes and half rhymes over full rhymes?

HGS: I only use rhyme when it will only come to me that way, and even then, I hesitate to use it. I have to think about it first. I ask myself, is this form going to help the message or hinder it?

Q: Are you a poet for whom the sound the words make is crucial?

HGS: It’s all about sound for me. I love alliteration. Sometimes a poem starts out with words that sound great together; they just come to me and I have to write them down. For instance, I was walking to a Queen’s University class at 8 a.m. one rainy spring day in Kingston, and couldn’t get this line out of my head: ‘These are the days, quickly melting away,” (from the poem EQUINOX). The poem took off from there.

Q: Would you accept Eliot’s contention that the subject matter is simply a device to keep the reader distracted while the poem performs its real work subliminally?

HGS: To some extent. But I don’t do it on purpose. It must be subliminal. 😉

Q: What role does humor play in your poetry?

HGS: I don’t try to be funny. I don’t try to be anything. I just write the way I think, and I think people find my honesty refreshing and humorous.

Q: What are your thoughts about accessibility and obscurity in poetry?

HGS: Accessibility is probably my trademark: something I’m proud of and at the same time it’s my tragic flaw, if you will, because I’m so accessible, many journals wouldn’t be interested. I’ve managed to get several respected online journals interested, and printed ones in the UK, and even a Canadian textbook company sought me out. I’ve been published in international anthologies, including a very special one memorializing 911–Babylon Burning, edited by the great Canadian poet Todd Swift–and in a few print journals in Canada, but not the most “elite” ones–the ones that have been around almost 100 years. I’ve kind of given up trying because I don’t think it’s that important to me any more. I want to touch real people’s lives; not just the academics. I want to write something that might comfort a stay-at-home mom or a couple struggling with their love/ marriage or a depressed person looking for a glimmer of hope in a fast-paced world. I think the people I’m trying to reach are more likely to happen upon my poetry on the Net, not so much in the special collections rooms of their libraries. I know that people can understand my poetry without having to go look in some reference book (except for the odd references I make to items in the news, and even then I try not to be obscure) and that’s quite odd. But I can’t change the way I write. I guess I’m destined to be a Fridge Poet – the one that makes it to everyone’s fridge beside their kids’ finger paintings. And at the same time, to help a few children in third-world countries get the education they wouldn’t otherwise get. That’s just fine with me.

Q: And the avant-garde?

HGS: I’d love to be avant-garde. I’d love to be Avant anything. Ahead by a Century. That’s cool. I think some of my poems are there (for instance, my collection Leap features the concept of the Status Update as poetry), others, not so much, and I guess we’ll see which ones stand the test of time in 100 years. Well, no, unless I live to be 137, I guess I won’t see that. But whether they’re set in a classic or innovative style, as long as my words can touch a few people’s hearts along the way…for me, that’s really all that matters.

Thanks for reading! —Heather Grace Stewart

many more children to school. As my daughter said when she first started walking: Go, Go, Go!

many more children to school. As my daughter said when she first started walking: Go, Go, Go!